Introduction

Reading ability is such an important skill in our modern society. Children, however, differ in their ability to read and understand written material and parents and teachers wonder why. The purpose of this article is to help parents and teachers recognize basic global patterns of reading ability/challenge within a specific group of children (i.e., those with an autism spectrum disorder). Awareness of the patterns can pave the way for more focused assessment of specific skills and provide a bridge to targeted support and/or instruction.

The Simple View of Reading

The topic of reading is so complex that many experts in the field of reading reduce conceptualization to a few key concepts such as:

- The essence of reading is the acquisition of MEANING from print (i.e., reading comprehension).

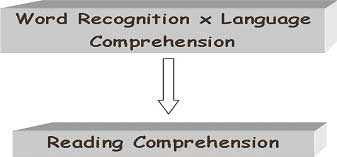

- Meaning or reading comprehension involves decoding or word recognition of words AND language comprehension.

This information is often displayed as a diagram called the Simple View of Reading which was first introduced by Gough & Tunmer and Hoover & Gough in 1986 and 1990 (Catts and Kamhi, 2005).

Establishing a Range of Differences

Within each of the broad categories of word recognition and language comprehension lays a continuum. If a little definition is added to the concept of a continuum, one might develop a visual graphic that looks something like this:

A Excellent B Average C Some Skills D Few or Very Restricted E No skills

Guiding questions might include qualitatively evaluating how well a student with ASD compares to age mates of the same cognitive abilities. Does he or she have the level of sophistication of skills of comparable classmates? Sometimes students with ASD have the basic skills but there are qualitative differences that might be important to note for programming purposes. If these difference are not noted and addressed through support and/instruction, individuals students may be headed toward frustrating experiences in school as they progress through the various grade levels which require increasing levels of sophistication with print. With this framework in mind, let’s examine the two components that contribute to reading comprehension ability.

Within the Simple View of Reading- The Role of Word Recognition

Word recognition involves the ability to quickly recognize a word. If one had to stop to decipher each word that one read, it would be hard to read and obtain meaning from sentences, paragraphs, pages, and chapters. One uses a certain amount of mental energy to decode unfamiliar words and the expenditure can vary depending on how difficult the reading task is for that person. Because quick recognition is the mark of a good reader, people typically develop a certain internal dictionary of sight words and apply strategies to identify the words that are not in their dictionary. Strategies might include the use of phonics, picture cues, background knowledge, or syntax to decipher or guess at unfamiliar words. For example, if the topic was trains, one might guess the word “freight” by mentally manipulating the word “eight” or from knowledge about trains and the syntactical cues (i.e., “The train had an engine and many freight cars”).

Underlying word recognition is a pre-reading skill called phonological awareness. This skill focuses on recognition of the sound system of our language and the ability to manipulate these sounds. It is not phonics or text based. Skills include the ability to rhyme, to tell what is the first sound in an orally heard word such as “bear;” the ability to name other words that start with the b sound from “bear,” the ability to synthesize a “k+ae +t” into “cat,” and so forth. Awareness of sounds in words is also helpful when one learns spelling. Even if spelled incorrectly, a child with good phonological awareness may be able to demonstrate the number of sounds he or she hears in a word. If one does not have this skill, then one is limited to memorizing the visual pattern of each word. Many children with ASD may have difficulty with this underlying skill.

Some children with ASD become good at memorizing sight words but don’t attach meaning to the words. When these children read, they sound like they have a large sight vocabulary. People can over estimate the child’s ability to read with meaning when based only on their oral reading ability. Most people would automatically assume that if a word is in one’s sight reading dictionary, that it is used with meaning. It would be easy to have inappropriate curricular performance expectations if one innocently but falsely made this assumption. These children with such good decoding skills are sometimes described as “word callers.”

Children who are at the extreme end of the continuum in terms of decoding words without meaning are called hyperlexic. These children are self taught in terms of these skills during the 2-5 year-old period of their lives. Some of these children move on to develop some level of comprehension skills while others may remain at a level of fairly meaningless decoding. It is possible that those who move on, may not have been as extreme, may have had better cognitive abilities, and/or may have had parent assistance to move toward meaning.

So, children with ASD can vary along a continuum in terms of word recognition. Before designing a program for a child, it will be important to know via assessment if his or her decoding ability is a strength or a challenge. If the latter, then the phonological awareness element should be considered. For some children, this might be a very difficult skill to completely master. Even mastering some basic elements might be helpful, however.

As gathered from the previous paragraphs, it is difficult to talk about decoding without talking about meaning as well. For example, when one is reading with meaning, one is attentive to phrasing. With the sentence, “The boy ran down the street?” “the boy” groups together as does “ran down the street.” One would not naturally pause between “the” and “boy” or “the” and “street.” One’s brain would register ahead of getting to the word “street” that it is a question and the voice should rise on the word “street” to suggest that this is an inquiry. Inflection and appropriate phrasing may not happen if one is reading one word at a time as an independent rather than an interdependent unit. This latter aspect of decoding is also called “fluency” but has a meaning element to it. Some children with ASD will not exhibit this recognition of meaning as they become smoother readers. Each word may be pronounced with the same inflection or emphasis pattern. This might be a clue to parents and teachers to check about meaning.

Within the Simple View of Reading—The Role of

Language Comprehension

Much of the message of oral and text language is expressed at the sentence level and through the inter-connectiveness of multi-sentences. Teachers and parents must be aware that some children only attend to the meaning of key words rather than the meaning of the sentence as a whole. Look at the difference in meaning from the sentence “The dog loved the cat’s bed.” When one looks at key salient words vs. the whole sentence, one might conclude that the dog and cat slept in some type of bed together when the dog really liked to safely use the cat’s bed when the cat was not around.

The strategy of attending to key words is not isolated to text comprehension. Oral language comprehension forms the foundation for reading comprehension. How well a child can express his message is not as important for reading comprehension as how well he understands the messages of others. With children with ASD, many children can be quite verbal but have real difficulty understanding and processing the language of others. Understanding the language of others simultaneously involves:

- Comprehending vocabulary including multi-meaning words and abstract concepts embedded within varying complexity levels of syntax.

- Understanding the requirements of question forms (e.g., “where” questions request location information and “why” questions request causal relationship responses).

- Understanding the significance of non-verbal cues; meaning of these important components of communication must be conveyed by words when one is reading a text format.

- Deciphering that the meaning intended is not as stated by the words (e.g., the language may be figurative because, for example, the person is really not the color blue today but is feeling bad).

- Noticing the vocal tone of the message that suggests that one is teasing or being sarcastic. For example, he sarcastically said, “Have a nice day,” as he walked away.

- Inferencing between missing information to extract meaning from the context.

- Determining the main idea of a message from the various chunks of information.

- Synthesizing the message to relay it to others.

- Understanding if the purpose of the entire message was to inform, criticize, tease, direct, deceive, etc.

- Understanding the bias factor underlying even basic sharing of factual information.

- Understanding roles, differing customs, experiences, personalities, etc. when that information must be conveyed in text without the support of the visual real-life context.

Unlike decoding, most, if not all, individuals with ASD will have some degree of challenge with various beyond-the-basics aspects of oral language comprehension. In turn, they will have difficulty with text comprehension. It is not just a processing or rate of information flow problem, but rather, an underlying problem that can relate to internal cognitive wiring, cognitive abilities, and social/ language knowledge.

The Simple View of Reading—Reading Comprehension

So, the outcome of using word recognition and language comprehension skills is reading comprehension. This applies whether one is reading fiction, nonfiction, poetry, advertising, text messages, or e-mails. The major advantage of text vs. oral language presentation for a person with ASD is that with text, the message is permanent, whereas a spoken message is fleeting and disappears. Text gives one time to think and to apply other strategies. One might go back to re-read, look up a meaning, go ask someone else for an interpretation, and so forth.

If one only addresses the end product of reading comprehension and does not pay attention to the other two components that underpin it, then one will be missing an important part of helping the child with ASD to improve. For example, many books on improving reading comprehension frequently do not identify the language component. The latter needs to be addressed in addition to comprehension monitoring and the learning of strategies that assist the reader to gain meaning from text. Certainly teachers and parents will want to help students or their children to be the best that they can be in terms of reading comprehension. It helps to have a good picture of what is involved and use that model to check out the underlying components.

Summary

So students with ASD can have strengths or challenges in either word recognition and language comprehension that will impact reading comprehension. Because of the understanding difficulties with the more sophisticated aspects of oral communication, similar challenges might be expected in reading comprehension when various elements must be conveyed within a written word format. Some students may have challenges at even a more basic level, however, in attending to the meaning of syntactical sentences.

Parents and teachers will want to assess, monitor, and track the word recognition or decoding skills and language comprehension skills of their students or children as they evaluate reading comprehension. Although problems with reading comprehension are to be expected amongst children with ASD, some of the problems may lessen over time with appropriate instruction and support.

Resources

Block, C. C., Rodgers, L. L., & Johnson, R. B. (2004). Comprehension process instruction: Creating reading success in grades K-3. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Catts, H., & Kamhi, A. (2005). Language and Reading Disabilities (2nd ed.). Boston: Pearson Education, Inc.

Craig, H. K., & Telfer, A. S. (2005). Hyperlexia and Autism Spectrum Disorder: A case study of scaffolding language growth over time. Topics in Language Disorders. 25(4), 364-374.

Grigorenko, E., Klin, A., & Volkmar, F. (2003). Annotation: Hyperlexia: Disability or superability? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 44(8), 1079-091.

Koppenhaver, D., & Erickson, K. (2003). Natural emergent literacy supports for preschoolers with autism and severe communication impairments. Topics in Language Disorders. 23(4), 283-292.

Israel, S. E., Block, C. C., Bauserman, K. L., & Kinnucam-Welsch. (Eds.). (2005). Metacognition in literacy learning. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Leekam, S. (2007). Language comprehension in children with autism spectrum disorders. In K. Cain & J. Oakhill. (Eds.). Children’s comprehension problems in oral and written language: A cognitive perspective. New York: Guilford Press.

Mirenda, P. (2003). “He’s not really a reader…”: Perspectives on supporting literacy development in individuals with autism. Topics in Language Disorders. 23(4), 271-282.

Nation, K. (1999). Reading skills in hyperlexia: A developmental perspective. Psychological Bulletin. 125(3), 338-355.

O’Connor, I. M., & Klein, P. D. (2004). Exploration of strategies for facilitating the reading comprehension of high functioning students with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disabilities. 34(2), 115-127.

Also see the IRCA Article in the communication section, Selected Bibliography: Literacy, for numerous references on various aspects of literacy (www.iidc.indiana.edu/irca).

Vicker, B. (2008). Recognizing different types of readers with asd. The Reporter, 14(1), 6-9.