Providing a predictable environment and routine is an important component of classroom programming for students on the autism spectrum (Iovannone, Dunlap, Huber, & Kincaid, 2003). Students on the spectrum may demonstrate rigidity or inflexible behavior if classroom scheduling is inconsistent or absent. However, it is impossible to avoid changes in daily activities due to school schedules, staff absences, weather changes, or human error. Along with unpredictable changes, staff members may find value in introducing students to novel settings, materials, peers, and activities throughout the school year to increase exposure to a broad range of experiences. When these changes in environment or routine occur, students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) may resist the new location or task, and may feel stressed, anxious, or confused (Kluth, 2003). Studies have noted that during times of transition or change, students are more likely to engage in tantrums, aggressive behavior, and refusal (Schreibman & Whalen, 2000; Flannery & Horner, 1994). This resistance to change may lead to difficulty in acquiring new skills.

Preparing students for the possibility of change, as well as the procedures that will be followed when change occurs, are vital tools in increasing successful transitions. Using visual supports throughout the preparation for new events and when teaching positive routines around change is also essential. Following are several visual strategies that can assist when introducing new activities to students and when preparing them for unpredictability.

Priming

Priming is a method of previewing information or activities that a student is likely to have difficulty with before the student is engaged in the challenging situation. A student previews future events such as a fire drill, substitute teacher, field trip, or rainy-day schedule, so they become more predictable (Schreibman & Whalen, 2000). Priming has been used effectively in academic instruction and social interaction (Harrower & Dunlap, 2001), and has recently been used in preparing students for novel settings or changes in routine. Two priming strategies that may be used to assist in preparing for novelty and that incorporate visual supports are discussed.

Modified Social Stories

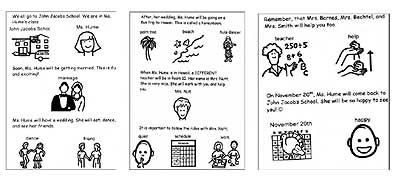

Social stories explain social concepts and situations in a visual format that may increase understanding for students with ASD (Gray, 2000). They are a method for explaining what is happening and what is expected across environmental settings. Typically social stories are written in first person, include illustrations, provide the perspective of a person with ASD, and should be at the student’s comprehension level. Often social stories provide answers to questions that students on the spectrum may not know to ask. Carol Gray, the originator of Social Stories, describes the recommended story structure and sentence types on her website, http://www.thegraycenter.org/. Though precise story structure is ideal, when faced with an unexpected change or novel event, modified social stories that can be quickly written by staff members (which do not contain an exact sentence ratio) are viable priming strategies. After identifying the novel event, and assessing the comprehension skills of the students, write a story following Gray’s guidelines. Staff members should read the story to and/or with the student consistently over a period of days. Providing a copy for use at home is helpful as well. When new activities are planned well in advance, preparing a social story following Gray’s guidelines is recommended.

Recent research (Ivey, Heflin, & Alberto, 2004) supports the use of social stories in teaching new routines and preparing for novel events. Social stories were read regularly to three young students with ASD as they prepared for several field trips to community locations. After reading the social stories for 3-5 days before the introduction of the new setting (attending a birthday party, going to a local pond, and visiting a gift shop), an increase in student participation and a decrease in challenging behavior were noted. Other examples of modified social stories used to prepare students for change or novel events follow.

Example 1: Preparing students for a substitute teacher.

Example 2: Preparing students for a school-wide parade.

Video Priming

Videotaped instruction has proven effective in teaching new skills to students with autism (Schreibman & Whalen, 2000), and recently has been used to prepare students for upcoming events. Because video viewing is often a preferred activity for students with ASD, and tapes can easily be watched before a new activity, video priming can be used as an effective strategy in introducing novelty to students. After identifying the setting or series of tasks that may cause anxiety or confusion for the student, go to the location with a video camera. Walk through the steps that will be required while taping and provide a simple narration about the process and requirements. Researchers recommend that tape length ranges from 1-4 minutes (Schreibman & Whalen, 2000). After completing the tape, view with the students several times over a period of days prior to the identified activity.

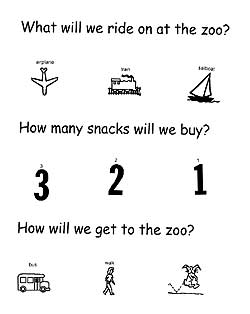

Research using video priming was conducted with several boys with ASD who demonstrated challenging behavior when going to new community settings with their families (i.e., Target store, Wal-Mart, Rite-Aid). The families videotaped several walking routes throughout the store (through the jewelry department, the toiletries section, toy department, ending at the cash register) and showed the videos to their children over several days. After the viewings, disruptive behavior decreased greatly as the routines were made more predictable (Schreibman & Whalen, 2000). Following are several video examples used when preparing students for a field trip to the zoo. Expectations that may have posed difficulty for the students (riding the train, using new restrooms, eating at the snack bar) were emphasized. When viewing the video, additional visual supports were used in to increase comprehension.

Example 3: Video priming for field trip to zoo.

Example 4: Additional visuals to support comprehension.

The Change Card

The importance of using visual schedules with students on the autism spectrum has been well documented in the literature, and well received by professionals (Harrower and Dunlap, 2001; Iovannone, Dunlap, Huber, & Kincaid, 2003). Schedules can be used to visually communicate upcoming events, facilitate transitions between activities, and increase student independence. Once students have begun to understand and follow a visual schedule, changes should be incorporated into the schedule content (Mesibov, Shea, & Schopler, 2005). The schedule should vary each day, and pre-planned activities should be deliberately changed in an effort to teach the individual to tolerate change. When activities are changed, however, a purposeful plan to support the student should be in place.

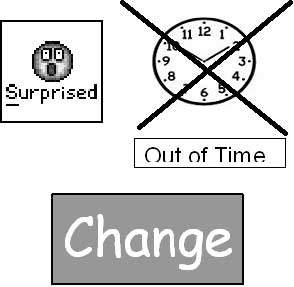

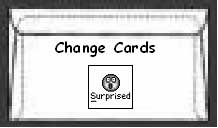

It is important to select a meaningful visual cue to use with students when introducing the concept of change. This can be a colored cue card, a “surprise” icon, a specific photograph or a written word depending on the needs of the students (see Example 5). Place the selected change cue on top of the scheduled activity that will not be occurring (i.e., recess on the playground), and the new activity next in the day’s sequence of events (i.e., watch a movie in the classroom). When teaching the change concept, it is helpful to go to the visual schedule with the student, look at the change card together, and assist with the transition to the new activity. Staff may choose to create a “change envelope” where the students can place the visual change cue and the schedule card of the activity that will not be occurring (see Example 6).

It is helpful to introduce change in a positive manner by first changing activities that are typically seen as non-preferred by the student to activities that are preferred (i.e., changing a student’s schedule from math to extra computer time). Then change can be introduced as a neutral event (i.e., changing math to language arts), and finally as something that may be difficult to accept (i.e., changing free time to work time). Often change is a loss of an activity or a staff member that is valued by the student, which can contribute to the anxiety and resistance to change that students may demonstrate. Systematically presenting change and novelty as a positive experience, and providing a supportive routine around change can increase student flexibility and participation in new activities.

Example 5: Visual cues to represent changes in a daily schedule.

Example 6: A location for change cards and schedule cards.

Instructional programming for students with ASD often emphasizes two core curriculum areas--social and communication skills. However, little attention is directed to assisting students in the third area of diagnostic criteria, restrictive interests and activities. Through the use of visual predictor strategies, students with ASD can learn functional routines, participate more fully in novel events, and as challenging behavior decreases, increase engagement and skill acquisition.

Additional Tips for Implementation:

- While many of the visual support examples use black line drawings (icons from Mayer-Johnson’s Boardmaker), this may not be most appropriate for all students. Assess the comprehension and understanding of your students prior to developing supports, since some students may require the use of objects or photographs to gain meaning from the cues.

- These strategies can easily be incorporated into the home environment as well (i.e., preparing for a new babysitter, explaining that a favorite DVD is broken, going to a different restaurant). Professionals may assist parents in identifying novel and challenging situations, creating materials, and modeling their implementation.

References

Flannery, K. B. & Horner, R. (1994). The relationship between predictability and problem behavior for students with severe disabilities. Journal of Behavioral Education, 4, 157-176.

Gray, C. (2000). The new social story book: Illustrated edition. Arlington, TX: Future Horizons.

Harrower, J. & Dunlap, G. (2001). Including children with autism in general education classrooms: A review of effective strategies. Behavior Modification, 25, 762-785.

Ivey, M., Heflin, L., & Alberto, J. (2004). The use of social stories to promote independent behaviors in novel events for children with PDD-NOS. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 19, 164-177.

Iovannone, R., Dunlap, G., Huber, H., & Kincaid, D. (2003). Effective educational practices for students with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 18, 150-166.

Kluth, P. (2004). You're going to love this kid. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

Mesibov, G., Shea, V., & Schopler, E. (2005). The TEACCH® approach to autism spectrum disorders. New York: Plenum Press.

Schreibman, L. & Whalen, C. (2000). The use of video priming to reduce disruptive transition behavior in children with autism. Journal of Positive Behavior Intervention, 2, 3-12.

The Picture Communication Symbols ©1981¬2005 by Mayer-Johnson LLC. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. Used with permission.

Hume, K. (2006) Change is good! Supporting students on the autism spectrum when introducing novelty. The Reporter , 11(1), 1-4, 8.