Adult Modeling of Communication Display Use

Learning to effectively communicate via an augmentative communication display or device can be challenging for any student who is nonverbal, minimally verbal, or a struggling but emerging verbal communicator. It can be an especially difficult task if the student has an autism spectrum disorder (ASD). These students usually lack role models who use an augmentative means of communication (AAC). In addition, adult caretakers may not always understand the complex demands and limitations of using AAC. This article will explore, primarily by example and description, selective aspects of ONE language intervention strategy called Aided Language. This article focuses on only one aspect of the adult role in an AAC intervention program i.e., how, during a planned activity, the adult may informally direct the student’s attention to:

- The physical layout, design, and mechanics of the equipment or AAC display (the physical layout may be a non-electronic topic board or a page within an electronic AAC device);

- The vocabulary and expressions featured on the display;

- The variety of communicative functions or types of messages that can be expressed within the limited display;

- The grammatical expression of ideas; and

- The strategies used to extend the expression of meaning beyond the vocabulary on the display.

For purposes of this article, a non-electronic topic board will be the vehicle for demonstration of Aided Language. Even if a student uses an electronic device for communication, some well known AAC interventionists such as Joan Bruno (2006), still use a non-electronic display to teach many of the skills mentioned above.

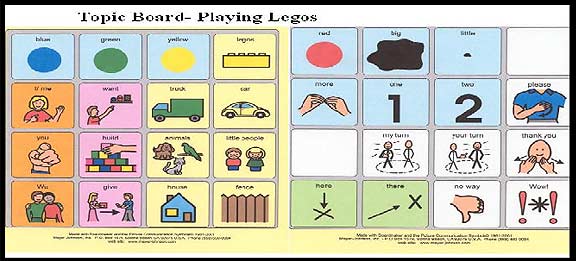

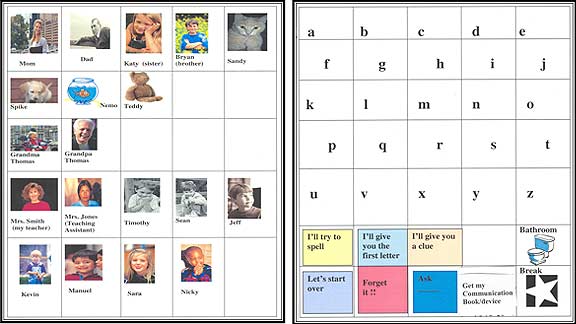

Creating an Activity Based Communication Display

Prior to the use of Aided Language on a topic board, an activity board or page must be designed. The speech pathologist, parent, and/or classroom teacher identify situations in which the child/student could use a more effective means of communicating messages. The vocabulary needed is selected on the basis of what would be useful for a highly interesting child-oriented activity and for the level of grammatical use to be encouraged. For example, for a child who is using single words, the goal would be to assist in developing two word utterances. That means that a display would need to contain object names, verbs or action words, adjective or descriptor words and location words. There may be other functional elements that one may also wish to foster. The next step is to organize the display of vocabulary. The topic board attached to this article is organized in a modified Fitzgerald Key format with groups of words classified by function. Each class of words also has a common background color which makes it easier for a child to recognize the location of a group of words and then the specific word needed (see the attached example board). Being able to find a needed word easily can help motivate the child’s use of an AAC display. A layout can be sketched with just handwritten words in a grid before actually doing a layout display using Boardmaker™ (a computer based collection of line drawing symbols and display formats). An adult may want to imagine use of the display during an activity by trying to communicate via the rough draft grid. Such an exercise might provide ideas for new vocabulary to add to the potential display. The topic board used in this article was generated on 3 separate pages with Boardmaker™ while the fourth page which contained pictures of people was constructed using digitalized photos. Two pages were joined to form a front and back display with enough vocabulary and pictures of sufficient size for a young communicator.

Communication displays can be introduced to some children who are as young as two years of age. What a display looks like in terms of number and type of vocabulary displayed, the size of the vocabulary squares, and so forth, depends to a significant degree on the strengths and challenges of the child’s language comprehension abilities and his visual discrimination abilities. On a non-electronic display, selective vocabulary can always be covered until the child is familiar with core or highly salient materials.

Adult Use of Aided Language

How an adult begins an introduction to a topic display depends on the individual child. The interaction might be very short and consist of singular demonstrated messages on the communication display by the adult during the initial stages. The child may have more interest in the display if he initially experiences getting something by using the display for communication. The expectations or task demands for the child can vary from the child watching what the adult does to communicate a specific request to the adult requesting the child to mimic, repeat, or rehearse the modeled message on the display. It is preferable to aim for flexible rather than scripted use, but the latter may be necessary with young communicators.

For an early communicator, the adult would only produce short modeled sentences. The adult does not need to have all of his words backed up by the vocabulary on the display. So the adult might say on his own behalf, “Want red Legos, please.” as he points to the word “red” on the display of a beginning AAC communicator. For the child with more language skills, the adult might present a more comprehensive grammatical model by pointing to each of the four words on the display.

It is preferable to let the beginner child watch on several occasions and then he or she might initiate on his or her own and possibly surprise you. This SLP learned that lesson with a 5 year old boy who had never used a topic board or a communication display. Access to any Lego pieces was under adult control. He knew his colors, so he was asked via speech and the display board if he wanted a “red” or “blue” Lego. Without prompting, he replied via the board that he wanted “green.” Within that instance, this nonverbal child with ASD demonstrated that he had some idea of how this system might work, at least for expressing a color preference. So, adults need to allow opportunities for spontaneous use instead of immediately teaching a scripted or fixed routine for an activity.

As stated earlier, these children generally do not have models of someone using their system, so allow for the possibility of the “aha” or sudden insight phenomenon. If, after several occasions, the child has made no attempt to use the display, the adult can then shift roles from the adult as a demonstration communicator to the adult as an instructor. He can tell the child, “Want a red Lego? Touch here.” (the red color symbol on the board) and hand over the colored Lego piece if the child touches the color symbol. If the child fails to act, the adult may want to repeat with a tap to the picture or a light physical assist to touch it, followed by delivery of the Lego. This dual role of demonstration communicator and instructor can persist throughout the intervention program.

Understanding how the various goals outlined earlier can be achieved with a topic board can be demonstrated by using a front and back panel of a topic board about playing Legos. What is shown needs to be within what the educator’s call the zone of proximal learning. This means the examples will stretch the child a little beyond what he might easily manage but without making the content too difficult to comprehend.